A loving mindset and the spirit of the law

0 Comments

Responding to God's Radically Inclusive Love

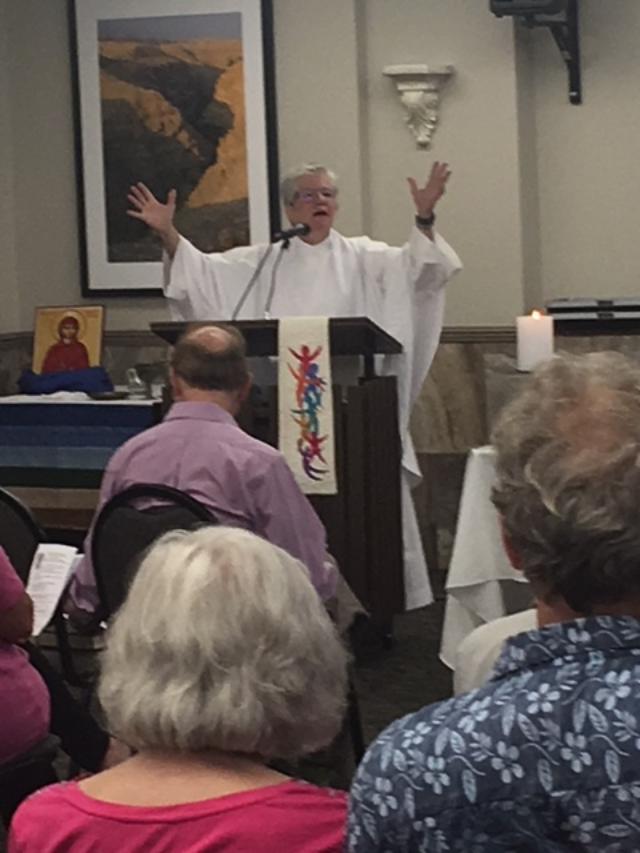

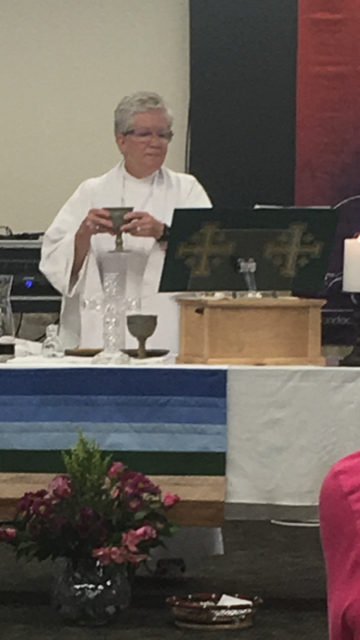

Helen Weber-McReynolds, R.W.C.P. January 15, 2023 Feast of Baptism & MLK Birthday Isaiah 42: 1-7; Ps. 40; Acts 10: 34-38, 44-48; Matthew 3: 13-4:1 I hope at least once in your life you have each had the experience of taking a deep dive into a lake or ocean, swimming for a nice long way underwater, and then coming back up to the surface for a huge breath of air. If you have, I hope the sun was shining brightly, so that when you came up from the darkness of the deep water, the light dazzled your eyes, and the water sparkled like diamonds everywhere all around you. I hope you made some huge splashes and felt the sun’s heat and the water’s cold, and felt at that moment really, truly, completely alive. To me, this is the idea behind baptism—surfacing from the dark and cold to begin a new, vibrant, re-energized life. To follow God with new passion and conviction. To leave behind destructive embedded beliefs and start fresh, celebrating God’s love by passing it on to everyone in your life. To greet a God whose love you know is secure and unlimited, like the God Isaiah spoke of in our first reading, when he said: “I am God. I have called you to wholeness. I will take hold of your hand. I will keep you. I have set you among my people to bind them to me. I have made you as a lighthouse to all nations, to open eyes that are blind, to free prisoners, to release dungeon-dwellers, and to empty despair of its captives.” This is the new life God calls us to—not just for one baptism, but every day as we recommit ourselves to help someone a little more, to listen a little better, to insist on justice a little more, or a lot more, and to try to deepen our relationship with God constantly. The story of Peter and Cornelius is one of my favorites of all the stories in the whole Bible, because it conveys so vividly the excitement the members of the early church felt when inviting other people into the radically inclusive love of Jesus. We have just the conclusion of this story for our second reading today. I encourage you to go back and read the whole chapter 10 in Acts. When we read about Peter and the other disciples going into Cornelius’ non-Jewish family’s house and passing on to them Jesus’ teachings, you can just feel the power of the Holy Spirit vibrating through everyone present. Peter himself had a major epiphany in that moment, realizing that, “God indeed shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who is humble before God and does what is right is acceptable to God.” He realized the Gospel was for Gentiles as well as Jews, for everyone who would accept it, and, for sure, that no one could withhold water for baptism for these people who had received the Holy Spirit. Martin Luther King, Jr. understood this radical inclusivity of God’s love very well. He was deeply convicted of the belief that racism and discrimination of all kinds is antithetical to Christianity. He knew and that God calls everyone, and that it is up to us to build the Beloved Community that God has established already and not yet. As Dr. King said in his I Have a Dream speech, “Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of (person)hood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children…. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black (people) and white (people), Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.” It sounds like baptism was a big epiphany moment for Jesus as well. From Matthew’s gospel we learn that when Jesus came to the surface after his submersion in the Jordan, he felt a tremendous affirmation, that he was God’s beloved, God’s own, with whom God was well pleased. It was such a profound experience that he had to go out into the wilderness for a long time of prayer and silence to figure out what to do next. He knew that being baptized with all the diverse folks who were coming out to the desert to hear John teach was the right thing to do. And afterwards he could feel the strength of God’s Spirit also, and a deep peace, as gentle as a dove. But what would the next step be? What is the next step for us? How do we continue our spirit-filled, re-energized baptized life? We are God’s beloved, God’s own as well. God promises to support us in every effort we take on to make the world better. Do we need some silence to help us figure out where to concentrate our efforts? Are we dazzled and disoriented by God’s profound acceptance? Or are we ready to take action right now? Mary's pondering

Helen Weber-McReynolds, RCWP January 1, 2023 Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God and World Day of Peace Numbers 6: 22-27; Ps. 4; Col. 3: 12-17; Luke 2: 13-19 You are awakened by the first few rays of morning light coming under the eaves of the barn. Joseph and the baby are still asleep. The floor is hard, though Joseph did his best to provide a soft bed of straw last night. The weather is cold, but the body heat of the cattle and sheep in this crude, small building have helped take off some of the chill. Thank God you and Joseph were able to find it, after you could not find anywhere else to stay last night. With the baby coming quickly, you were desperate. And now the baby you carried all those months is here, and he is so beautiful. The only bed you had to lay him in was a feed trough there in the barn. But lying there, so peaceful, so perfect, you are proud and hopeful. The delivery was nothing like you had planned. You were caught short, the baby coming suddenly while you and Joseph were still traveling. Your whole betrothal and then this unexpected early pregnancy have been so sudden and unplanned—how did you come to this moment? What does it mean for the future? You have been raised by your parents, Anna and Joachim, to understand that, as a member of God’s people, you have a responsibility to help bring awareness of God’s profound love to the world- to help spread justice and loving-kindness, especially to the poor, the migrant, the widow, and the orphan. All your life, you have rejoiced in God’s love and reveled in the beauty of God’s creation, treasuring your moments wandering the olive groves, wading by the lakeshore, and gazing at the stars in the sky at night. Though you never had the advantage of formal education, you have soaked up as much oral history of your religious tradition and memorized as much Hebrew scripture as possible. You know by heart the prayer of your ancestor, Hannah, and you love the parts about God lifting up the lowly and feeding the hungry the most. You have devoted yourself to prayer and Jewish teachings. You are determined to serve God. Your whole life has been one long “Yes” to God. But you live in a land now occupied by the Roman Empire, where violence, cruelty, rape, and taxation enforce submission and poverty. The urgency of God’s message to help find justice for your oppressed community seems greater than ever. Rebellion seems to simmer just below the surface always. You and Joseph have looked forward to marriage and starting a family. When God seemed to offer a less conventional plan, you still said “Yes.” You knew you were in danger, but you were not afraid. You have faith in the limitless love of God. After many months of prayer and reflection, with the support of your cousin Elizabeth, you have been inspired to believe that God has something very special in mind for your son and your little family. Just last night, some shepherds came to the door, saying they had a message from God that the baby born there had been sent by God to be the savior of his people, descended from the great king David. What does all this mean? What does the future hold for you, for Joseph, and, most of all, for Jesus? With faith in God, you understand that the future will unfold as it will. But you resolve to help your son prepare the best you can. You say “Yes” to modeling God’s love for him, to teaching him God’s word, and to showing him every day how much God loves everyone. God has given you a precious, special son. Your life’s work will be helping him to live in God’s image. The baby is starting to stir a little now. As you lift him from the manger, you whisper a prayer asking for God’s help in doing what is asked of you. This child is love and will be love. From this day on, you will teach him only peace. Helen Weber-McReynolds, RCWP

December 4, 20222 2nd Sunday in Advent Isaiah 11:1-10; Ps. 95; Romans 15: 4-13; Matthew 3: 1-12 Dorothy Day said, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” I think she didn’t want people to sell themselves short, thinking that there was no way they could help the poor and wage peace as she did if they weren’t perfect. I think she also wanted to be known as a radical, a rabble-rouser, someone who protested the injustice in the world, and who worked to create positive change. And she wanted other people to do the same, to be critics and protestors of injustice, but then to do whatever little bit they could to make themselves and the world better, and not worry about being saints. I think Isaiah, Paul, and John the Baptist are all calling us in a similar way in today’s readings. They are calling for all of us to be rabble-rousers in faith. But what kind of radicals are we called to be? Isaiah, in this beautiful holy mountain passage, says the kind who search for justice for the poor, equity for the meek, and who are bound by truth and righteousness. Paul, in his plea for unity between Jews and Gentiles, calls us to be servant-leaders to everybody, to model inclusion in the image of God’s radical love of all. And John the Baptist calls us to prepare the way of God, to make straight the paths in our communities for all to participate in the joy of God’s love, to invite everybody to the river of new life. Advent is a good time to settle down and reflect on being a better person, and leader, individually. But I think these three prophetic voices call us even more to work communally as the people of God to make Jesus come alive again in our statement and actions. Our Gospel translation today uses the word repent, but the Greek word it came from is metanoia, usually translated, “to change your mind.” We often associate repentance with guilt, with paying a penalty for past mistakes. But John was calling people to baptism, not to punishment. He was inviting people to a begin a new life. He was encouraging people to submerge themselves in the Jordan and leave their old mind-set behind, and to come to the surface with a new attitude, to adopt a new, more loving, inclusive, justice-oriented way of thinking. He invites us, just the same, to puzzle through together, as the people of God, how to work toward peace, for one another, and for our earth. And John said he was the forerunner of one even more life-giving, more merciful, and more wise. We know that he was leading the way for Jesus, the human presence of God, through the consent of Mary. Jesus personified God’s acceptance, inclusion, forgiveness, and love, not punishment or guilt. Jesus and John call us to consent, as Mary did, to bring forth in our own lives peace-making, help-giving, and loving kindness. So as spiritual rabble-rousers, as riverside prophets, as everyday communion-builders, what are we being called to say? What are we being called to say to our government, as Americans? What are we called to say as citizens of Indianapolis? What shall we say to the Catholic church, as members striving for reform and renewal? What will our statement be, by example and action, to the people we work with? Our relatives? Our friends? We are called to be critics, of course, of what we see as wrong. But the Gospel we live by is the Good News, and our Creator is a God of love and mercy. I invite us to be Advent people, to foretell a better future by working to come up with new, creative ideas to make things better. Certainly, membership in an RCWP community gives us “wild shoot”, rabble-rouser status. And I think that what we are doing here, trying to create a new way of being church, modeled after the old way of the Early Christian community, which is inclusive and non-hierarchical, is a big step in the right direction. I challenge us all to constantly grow spiritually, teach one another and keep learning constantly, and keep working at all the things we each do to make things better for our human family members and for the earth. We are preparing for the Advent, the arrival, of the Christ, the life-saving event of human history, the shared destiny prepared for all of us by God when we were created in the divine image. We have a new, hopeful, loving, justice-filled story to tell. Let us answer the call to be the flower of Jesse with words and actions of protest and of peace. Conduits of LoveHelen Weber-McReynolds, RCWP

November 6, 2022 32nd Sunday in Ordinary Time 2 Macc 7: 1-42 abbrev; Ps. 16; 2 Thess 2: 16-17; Luke 20 27-40 You may have heard me talk about my family’s annual Metzger Reunion, every Labor Day weekend, a 4-day affair attend by around 250 people. This year was our 95th Reunion. It is always the highlight of the year for our family, because we love seeing one another, and it’s a fantastic party. But some of the best parts about it are thinking back to the ancestors who started the Reunion. Having just celebrated the Feasts of All Saints and All Souls, their spirits seem close. As immigrants, they were eager to preserve family unity and keep alive the memory of past generations. They were generous, hard-working souls, who passed on the ideas of sharing with whoever needed help, staying close to God as a family, and actively engaging in local politics, to make sure things were fair for everyone. At the Reunion we remember our ancestors, by singing songs and tell stories about them. And by offering up prayers to them at a service on Sunday morning, including singing a litany listing all our deceased members. We want to keep these charitable, fair-minded folks alive in ourselves. We want them to live on in us by being kind and doing what’s right ourselves. To me, our readings today center on the same idea, of keeping alive the spirits of charity and justice. As Christians, we are resurrection people. We believe Jesus the Christ is still alive, having risen from the dead, so that his Spirit and teachings can continue forever. In us, the ideal of the unconditional love of God continues to work, continues to strive, as we labor to establish the Beloved Community. Jesus told us that the Kingdom of God is among us, and our job is to build up that family of love, to make it accessible to everyone. Our first reading recalled a strong, holy mother, and her seven sons, fighting for their religious freedom, against an empire that was trying to wipe out the Jewish nation, and its teachings about carrying on God’s love by caring for widows and orphans, and making sure everyone had what they needed. These Maccabean family members were willing to die for these teachings and their Jewish heritage, believing God would raise them up and keep their lineage of faith alive. They believed they would not die in vain- they would be alive in God to inspire future generations to keep God’s law of love. In our Gospel, Jesus echoed this idea of eternal life in God, building the reality of God’s love, generation after generation. The Sadduccees believed God’s covenant meant that reward or punishment would be meted out during life on earth, and there was no afterlife. They were intent on accumulating wealth and heirs on earth, and they saw wives as instruments of procreation. So they issued Jesus a trick question- whose wife, after seven husbands, would the woman be in the hereafter? As usual, Jesus refused to fall for their ruse, but got straight to the point of the meaning of life for us: we are here to live the love of God, on earth and forever. He said that God is the God of the living, not of the dead. All are alive in God. Jesus said that Moses believed this and it is central to our faith. Marriage is a construct important on earth, but we will not need it in our resurrected lives. We will all be one in God’s love. In our second reading, Paul’s follower encouraged us to let this hope of resurrection energize our lives, to let it comfort, refresh, strengthen, invigorate, and enliven us, as we keep working to build the Kin-dom, day by day. Theologian Barbara Holmes said, “We live in a world saturated with the love and intentionality of an ever-present God, and we are not alone.” We are destined for life after life, and God is always here to encourage us to live and love as abundantly as possible. Our ancestors surround us from their resurrected lives, in their oneness with God, and in their hopes for our continual transformation. Our ancestors are alive in us, or they can be, if we choose to be conduits of their flowing love, the love they learned from God’s love. All the kindnesses and unselfishness, all the times they stood up for justice for others, all the times they shared with us or other people- all that love flows down to us and can flow on out to the world, if we choose to let it. And we can be examples to our children and friends, to keep the loving flowing for generations to come. We can live forever in them, in God, in the earth, and in love, as it flows on and on. 25th Sunday in Ordinary Time, September 17, 2022

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed